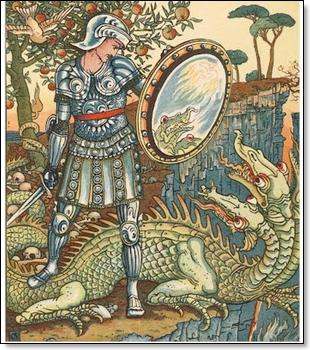

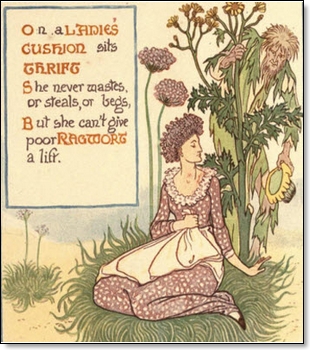

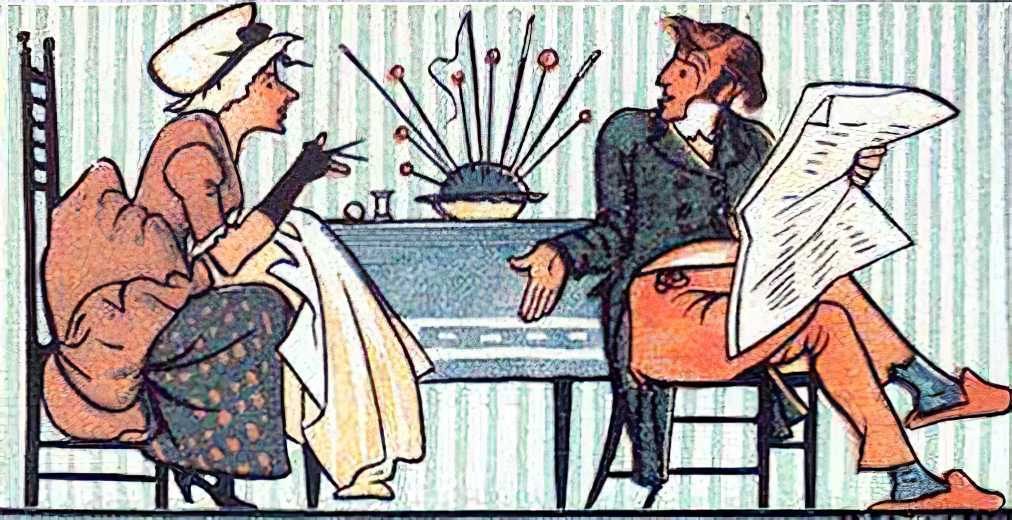

Walter Crane and other artists in his circle such as William Morris were pioneers in the development and popularization of decorative art. Decorative art is a movement which transccends medium and form and is equally applicable to wallpaper as o fine china or utilitarian objects. It aims to pair art and beauty with everyday objects. Below is an in depth disucussion of Decorative Art and its development.

Decorative Art is fine art applied to the ornamentation of objects which exist for other purposes than beauty. Thus the hilt of a sword consists of grip, pummel, guard, etc., and needs no ornament, having indeed a certain beauty of its own from the fitness of its parts and the color of the metal, etc.; but if it receives embossing and chasing, or damascening, or even an elaboration of form not required by utility, then the fine art employed in beautifying it in these ways is decorative art. By extension the term is used for the various fine arts of less developed and less dignified character; thus a statuette carved in wood and painted, or one made of Dresden porcelain, is often spoken of as a work of decorative art, although the statuette serves no purpose except as a work of art; but a life-size statue would not be called a work of decorative art, nor would even a statuette of bronze or ivory be called so except erroneously, and because it may serve to decorate a room. So a painting on canvas is not spoken of as decorative art, but one on a porcelain plaque is so spoken of, though it serves no purpose but that of a picture. This extension of the term comes from the employment of those materials or those means of ornamentation which are commonly used for decorative art proper. Thus, in the cases just now given, carved and painted wood is so much used for ornamenting useful things, such as buildings and parts of buildings, furniture, and the like, and porcelain is so much used for unornamental dishes, bowls, and cups, that these materials and the ornamentation generally applied to them give the character of decorative art to anything in which they are used.

The chief of the decorative arts, or the chief manifestation of decorative art is what we call architecture -- that is, the making a work of fine art of a building which, if purely utilitarian and without any application of fine art to it, would be equally useful as a building. But the kind of fine art used in making a building beautiful by means of the proportion of its parts, its generally graceful form, its picturesqueness or its tranquil majesty, its lightness or its ponderous solidity : and also by means of the leafage, the animal or other forms added to it in relief, inlay, etc., is exactly the same as that used in the sword-hilt, cited above. In times when art was great the same man would design a palace and a bronze medallion and a silver flask for priming-powder; moreover, the same man would paint a sacred picture on a church wall and a coat-of-arms above a mantelpiece. Not that much good decorative art was not produced by artists of secondary rank, for undoubtedly the greater number of ornamental weapons and pieces of furniture were made by men who did not make statues or paint frescoes on church walls; but there was no sharp and generally seen distinction; the statuary was the more skillful carver, the religious painter was the painter of bridal chests and armorial shields grown stronger and more skillful, and now generally recognized as a master.

Decorative art may be divided into classes and groups of classes as to the materials employed or as to the articles and objects adorned. Usually a twofold classification is adopted. Thus in a great collection, which has now (1893) been dispersed, the classification was under thirty-six heads for mediaeval or later objects alone. Sometimes the material determines the title, as leather-work or ivory-carvings; sometimes the destination of the objects, as arms and armor, or coins, medals and counters, or church goldsmiths' work. To this list of the classes of European objects for a term of eight or nine centuries only would have to be added the lacquers of Oriented art, the lapidaries' work in very hard and costly stones of both Oriental and Western nations, bookbinding, the mosaics of antiquity and the Middle Ages, the architectural inlays of stones, etc., of different colors, the glazed and other pottery used in architecture, the painted vases of the Greeks and their imitators, the painting of architecture in bright colors used by Egyptians, Greeks, and mediaeval artists alike, and the whole immense world of architectural sculpture, in all ages and all lands.

The field is vast, therefore. In fact, all the graphic and plastic arts are decorative when used for decoration, and they have been so used far more than in any other way. (See Fine Art.) When savages begin to make simple weapons and simple utensils, the disposition to adorn them in some way shows itself almost from the beginning. And this adorning is partly by adding color or sparkle, as by means of pretty bits of shell or stone or bright feathers, to the weapon or the utensil, and partly by carving it, as by cutting rows of notches, sinking circular pits, engraving wavy and curling lines, and the like. But this coloring and. carving is also connected in a curious way with the attempt to represent beasts or birds or men. The inlaid bit of shell is often made to look like an eye; the wooden point of a spear is sometimes worked to look like a tongue projecting from a mouth; even the stiff and rectangular patterns made by weaving together coarse fibers of different colors are forced into some semblance of the human figure or of some beast of chase. All this is decorative art, and this is the only art known to primitive people, because they have not begun yet to make pictures or bas-reliefs in our sense. All the artistic power of the primitive people is given in this ornamenting of spears and paddles and tappa matting and plaited grass; but this ornamenting itself involves a constant attempt to represent the living creatures about the artists -- that is to say, the things they care the most about.

Now this is very nearly descriptive also of the condition of fine art in a community of the relatively high civilization of the European Middle Ages. In the thirteenth century in France and England there was still the same turning of all the artistic feeling of the time to ornamentation. No bas-reliefs were made except to fill the tympanum over a door or to adorn the back of a small round mirror or the like; no statues or statuettes except to form a part of the relics of a saint; no picture of men and their deeds was painted except as an acknowledged and, in a sense, necessary part of the decoration of a building or a piece of furniture. All the fine art of such a time is decorative art; and as a result, the best artistic thought of the time goes into decoration.

The wonderful results of this concentration of thought are seen not only in the decorative work of the time, but long afterward. Thus in the fifteenth century in Italy, although pictures and statues were produced which can not be classed as decorative art, the decorative art itself was kept up to a very high ideal. This is the result of tradition; the best artists of the Italian Renaissance had little time to think of jewelry and bookbinding, for their time was taken up with still nobler applications of their power; but the demand for high excellence in decorative art, once established, was slow to cease, and therefore there were still very able men ready to take up these arts and pursue them. At last, however, the demand for such excellence did cease; the high standard was lost. It is a very difficult subject of inquiry why the natural and healthy taste for ornamentation gradually disappeared in Europe, until the French Revolution suddenly destroyed it, and left the European world with no beauty of costume, no natural architecture, no humor for ornamenting. The first half of | the nineteenth century went by with but little sign of improvement; but in the second half there has appeared to be a self-conscious and deliberate effort to recover the feeling for decorative art and the power over it which the people of earlier times had held naturally as a part of their intellectual equipment. The predominant commercial spirit of the time has been, however, directly opposed to any such recovery, and the changes of fashion, largely caused by the commercial spirit, have prevented continuous and natural development of any style.

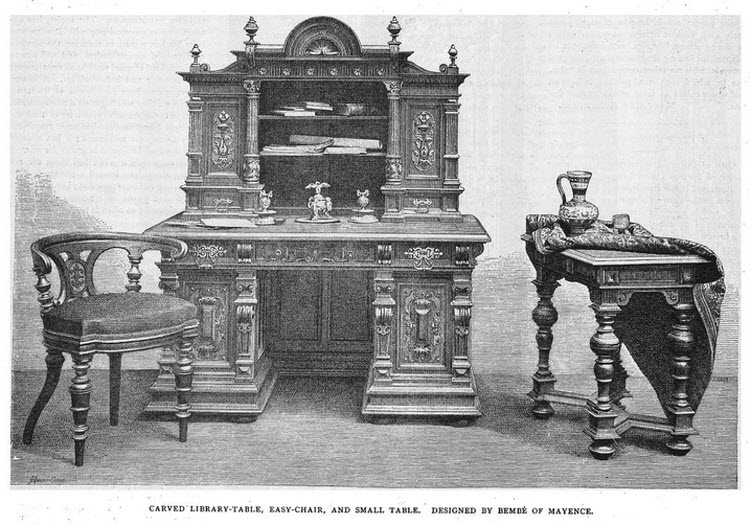

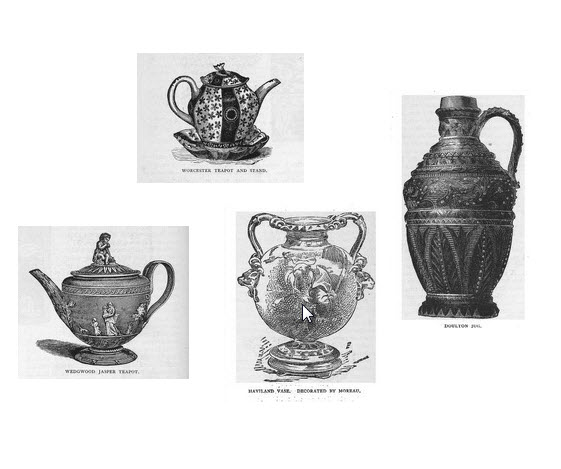

Among people of European civilization, toward the close of the nineteenth century, decorative art is commonly looked at from two very different points of view -- the collector's and the constructor's or designer's point of view. All portable objects of art, such as vases of porcelain and of bronze,painted dishes, enamels on metal, stuffs and embroideries, and the like have been for fifty years the subjects of a minute and really scientific study and investigation which has resulted in an historical knowledge of them which no other age of the world has ever possessed. In fact, a large part of the new science of archaeology is devoted to these smaller works of decorative art. Immense and costly private collections have been formed, and are perhaps richer in the aggregate than the national museums, especially in containing more of the exceptionally fine and very unusual pieces. Enormous prices are given for such pieces; and this is so far fortunate that it has caused the preservation of many valuable things which would otherwise have been destroyed. Collectors, then, will buy ancient works of art, vases, carvings, bronzes, and the like, rather than modern ones, not only because they are generally finer, but also because they are more easily understood and classified. There are hand-books and dictionaries and also more elaborate treatises to which to refer for ancient art, whereas the work of to-day has to be judged upon its merits, and few persons feel themselves competent to do that. To possess a known and classed ancient work of art, described in the books, or of a kind so described, is more than to have a new piece, however fine. This fact is a serious hindrance to the growth of modern decorative art in portable objects, as there is little encouragement to the maker or the dealer. And here again modern commercialism intervenes to hurt modem art. Any increased respect among buyers and students for modem design is prevented by the disappearance of the art-workmen among a crowd of employees in the shop of a large dealer, and the consequent lack of intercourse between the designer and the employer or paymaster. Moreover, in the organization of a large establishment the designers are separated from the workmen who carry out their designs, and the few instances of fine and original work have generally been obtained by deliberately reversing the ordinary commercial methods.

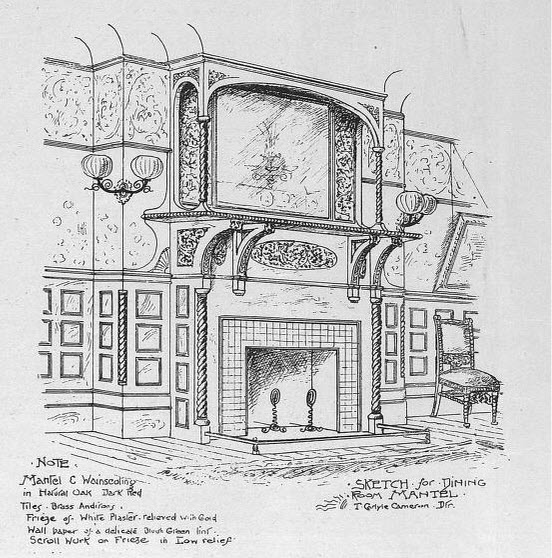

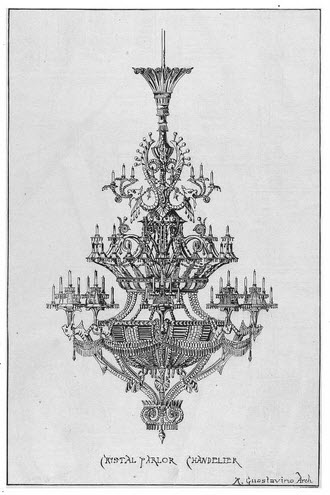

On the other hand, the decorative art of building-—that is to say, the architecture -- of the nineteenth century is almost wholly a matter of copying from ancient buildings. Not only is the style of design, in the general mass and in detail, closely followed, but the ornamental details themselves are copied very exactly, far more often than composed anew, or with any degree of originality. An immense number of excellent books on ancient architecture were published between 1850 and 1890, and photographs have been made in abundance, and are to be bought very cheaply. If a panel of a given shape has to be filled with scroll-work, it is easy to find a photograph of a panel of very nearly the same shape, of fine ancient work of any style that allows of such panels at all. It is far easier and more certain and simple to copy this with such slight modifications as the shape calls for, or as considerations of expense may bid, than to strive for any originality at all. As for the general design of a building, that can not well be copied so closely in most cases, for modem requirements are very different from the ancient ones; but ancient styles are so closely followed, now one style and now another, that no opportunity is afforded for sufficient consideration of the proper form and the obviously natural decoration in any new building, and there is none of that freshness of thought and of inspiration which comes from allowing the design to grow naturally out of the necessities of the case. No style of architecture has ever arisen except when all builders were following the same manner of building and the same fashion of decorating. Slowly, for centuries, an old style, which all the builders and artists of the day were using, as a matter of course, has undergone modifications as the result of new requirements and new ideas, until some unusual opportunity has offered and a new style has developed itself rapidly. Never before in history was a time known like the years from 1840 to 1890, when one designer imitates one style, one another, and only a few exceptions exist of men or associations who are trying to design independently and naturally. This state of things has been almost universal in architecture proper throughout all that long period; not quite so general in stained glass, decorative painting, pottery, furniture, and the like, it is the rule even in these. Nor does it appear that there is sign of improvement. See Fashion.

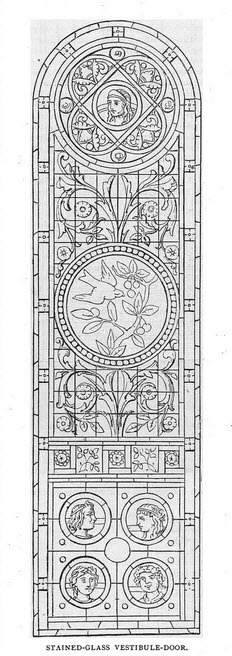

The above attempt having been made to explain the admitted deficiency of the modern European nations in the matter of decorative art, it remains to be shown what there has been done during the latter part of the nineteenth century which is more encouraging; and, first, it must be remarked that the workmen who can design, upon whom Oriental and ancient decorative art has generally depended, exist no longer in Europe or America, and that no design can be got except from artists of special, deliberate, and costly training. Stained glass for windows is the one branch of decorative art most successfully practiced in America, and the most important part of this is produced by half a dozen painters well known as artists of high rank, and who, if they were not engaged in the stained-glass business, would be producing easel pictures which would bring high prices. Modern wall decoration which is of any value consists of fully realized paintings by artists of just such high rank. Modern architectural sculpture not merely copied from work is of a wholly different character from that of past; the foliated capital, the frieze of scroll-work the conventionalized beast or man of ancient work are replaced, the few modern buildings that are treated with respect enough to have rich and costly sculpture, by statues of complete scientific excellence, set up in niches or between windows. In all these, representative and expressive art of skilled and highly taught artists, and of technical excellence approaching the highest, has replaced the effective decoration of the artisan working according to tradition So when a modern manufacture of pottery begins to be artistic, it becomes so by means of painting, as of flowers and leaves, so faithfully studied from nature that it differs from similar work on paper chiefly in the limitation of its coloring. A vase will be ornamented by means of a sprig of chrysanthemum or rose seeming to be laid upon the body and neck, and the painter makes this as like the natural sprig as his means and his ability allow. The vase itself will be very simple in form; indeed, it is very curious how little diversified and how simply modeled are all these richly painted modern vases. The naturalistic sprig or bouquet laid upon it is its only decoration beyond a generally graceful form and a pleasant color and texture of surface.

And evidently it is in this way that modern designers ought to proceed. There is the line of least resistance which all ought to follow. The most accomplished European artists are unable to design in meaningless patterns, scrolls, frets, and zigzags, or in conventionalized and formal hints at animal and vegetable forms, as the humble and unknown artisans of Europe once designed, and as those of the East were still designing until a few years ago. They can not produce shawls like the people of Northern India, nor painted plates and vases like the Chinese, nor varnished boxes like the Japanese, nor rugs like the Persians. Not only is Europe incapable of these beautiful arts, but European influence is destroying them rapidly in the lands where they are native. The only chance for any decorative art is to employ the trained painter and sculptor, and to allow to them this innovation, that great simplicity of form and color shall alternate with fully expressed art of representation and expression, no lower kinds of art being possible to us.

Leading figures in the decorative art movement include Walter Crane and William Morris.

-- Adapted from an Article by Russell Sturgis, from the Century Cyclopedia, 1885